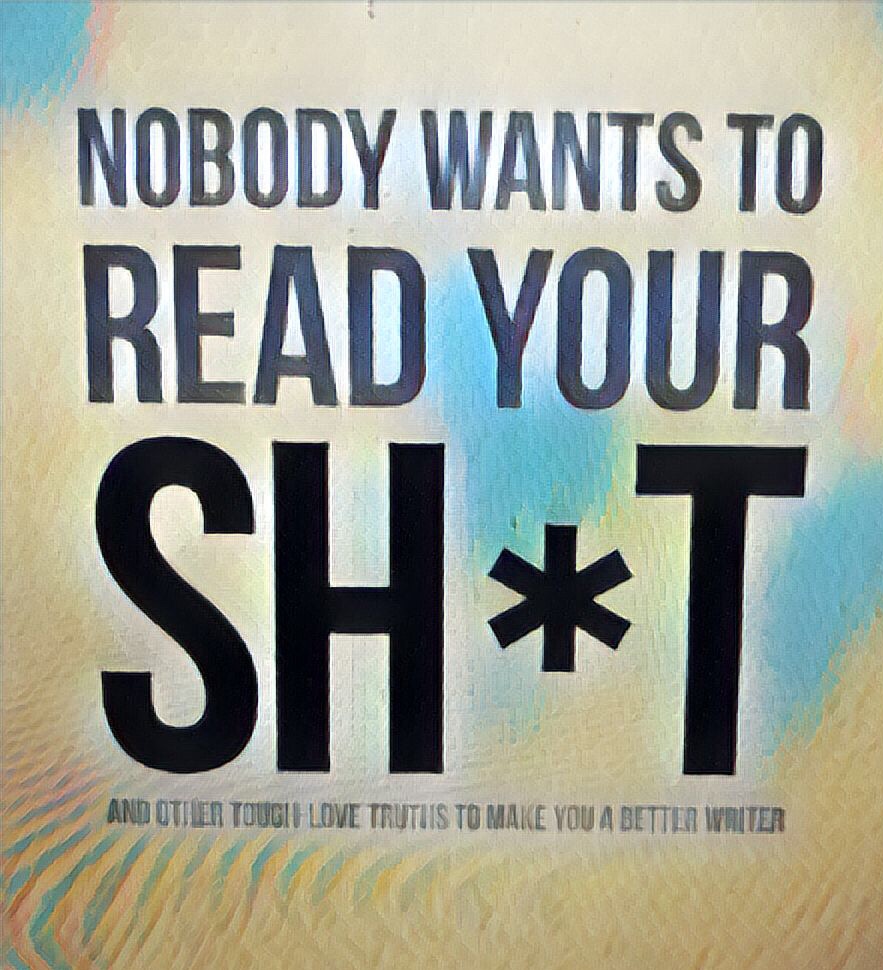

“Nobody wants to read anything,” Steven Pressfield notes at the beginning of No One Wants to Read Your Sh*t And Other Tough Love Truths to Make You a Better Writer.

“Let me repeat that. Nobody – not even your dog or your mother – has the slightest interest in your commercial for Rice Krispies or Delco batteries or Preparation H. Nor does anyone care about your one-act play, your Facebook page or your new sesame chicken joint at Canal and Tchoupitoulas.

It isn’t that people are mean or cruel. They’re just busy.

No one wants to read your sh*t.”

This week, I’m delving even more into the work of Steven Pressfield because rarely have I found a self-help author who is so real about the creative process. In No One Wants to Read Your Sh*t, he develops many of his ideas further; what I especially like about this book is that, as the screenwriter of The Legend of Bagger Vance, he shares some invaluable takeaways about the medium.

I’m sharing my favorite nuggets here (with and without commentary).

Getting Over the Hump

“A real writer (or artist or entrepreneur) has something to give. She has lived and suffered enough and thought deeply about her experience to be able to process it into something that is valuable to others, even if only as entertainment.

A fake writer (or artist or entrepreneur) is just trying to draw attention to himself. The word “fake” may be too unkind. Let’s say “young” or “evolving.”

That was the hump.

To get over it, a candidate must grow up. A change has to happen at a cellular level.”

-Chapter 34

My thoughts: In my younger years, I’ll admit that I think I was chasing The Dream of Wealth and Fame from Screenwriting. Now, I feel like I’m chasing the High of Having Written Something Today. Am I more real today than I was then? Dunno. But I sure feel happier.

Three-Act Structure

“Break the piece into three parts – beginning, middle, and end.

Why is a three-act structure essential in a movie?

Because a movie (or a play) is experienced by the audience in one continuous block of time. It’s not like a novel or a piece of long-form nonfiction, which may be picked up and put down by the reader multiple times before she finishes. With a movie or a play, the audience enters the theater, settles in for ninety or 120 continuous minutes. You, the writer, have to keep them riveted in their seats for that length of time.

How do you do that?

By hooking them (Act One), building the tension and complications (Act Two) and paying it all off (Act Three). That’s how a joke is told. Setup, progression, punchline.

It’s how any story is told.

Have you ever tried to seduce anybody? The hook, the build, the payoff.

Ever tried to sell somebody something?

Ever gotten into trouble and tried to talk your way out of it?

The hook, the build, the payoff.

Euripides worked in three acts. Shakespeare did.

Do you know something they don’t?”

-Chapter 37

Every Story Has to Be About Something

“What does it mean, “to be about something”?

Hamlet is about something.

The Godfather is about something.

The Walking Dead is about something.

Beneath the car chases and the sex scenes and the special effects, a book or movie that works is undergirded by a theme.

A single idea holds the work together and makes it cohere.

Nothing in that book or movie is not on-theme.”

-Chapter 47

My thoughts: When I served as an SAT/ACT tutor (for 14 years), I used to explain to my students the difference between subject and main idea: subject is what it’s about on the surface (i.e., Moby Dick is a novel about whale-hunting on the surface) whereas main idea is what it’s really about (i.e., what we sacrifice when we pursue a gigantic goal). Here, concept feels analogous to subject; theme is like main idea.

The Second Act Belongs to the Villain

“The villain in Silver Linings Playbook is internal. It’s Bradley Cooper’s obsession with getting back together with his wife Nikki. By the end of Act One, Bradley has met Jennifer Lawrence. Clearly she loves him. Clearly the two of them are made for each other. Will Bradley blow this potentially great thing with Jennifer because he’s so obsessed with getting back together with his estranged wife?

TIFFANY: Tell me about this Nikki thing. This “Nikki Love.” I want to understand

The movie comes back to this Monster again and again through Act Two. No action hero was ever invested more with dread of a villain than Jennifer Lawrence is of this antagonist that exists only inside the skull of the troubled young man she’s in love with. Her pain and jeopardy throughout Act Two keep us riveted and rooting for her.” Keep the villain up front throughout the Second Act.”

-Chapter 51

My thoughts: I had never thought about the second act belonging to the villain before, but it totally makes sense. The second act is generally where the protagonist suffers, so it would make sense that the (internal and external) antagonists own it.

Start at the End

“Begin with the climax, then work backward to the beginning.”

-Chapter 54

My thoughts: Such. great. wisdom. Too many screenplays lose momentum around Act Two/Act Three because the writer has written himself/herself in a corner. Best to think about the end first and write to that.

Text and Subtext

“The greater the contrast [between text and subtext], the more powerful the emotion produced in the audience.”

-Chapter 59

Digression: Hollywood Storytelling

“The story principles you learn in Hollywood share one primary quality:

They’re very American.

Why are French films, or movies made in Japan or Iran or Israel, so different from homegrown US pix? Because foreign stories arise from alien waters. The filmmakers don’t share the same assumptions that we Yanks do.

- American movies believe in the American Dream. American stories start from the ground of freedom and equality. To us, these elements are universal. We take them for granted.

American stories buy into (and sell) the American dream – you can be anything you want to be if you’re willing to work for it. And they deal with the American nightmare – what if we try and fail?

[Pressfield goes more into how these movies are essentially our culture, not anyone else’s for a bit, but I’m not including it all here]

- American movies believe in cause and effect.

De Tocqueville called us a “race of mechanics.” We invented the steam engine, the cotton gin, the flying machine. We understand gears and pulleys. We know how to use a socket wrench.

The American Dream is mechanical too. It believes in justice. If you and I work hard and play by the rules, success will be ours. This is an article of faith in the States (and is believed as fervently by each wave of immigrants flocking to U.S. shores)

American movies reflect this optimistic belief. Just as you and I can fix our Ford V-8 if we faithfully apply the laws of mechanics, so too can we find the love of our life, bring the villain to justice, save the planet from apocalypse. We just have to solve the problem. As Tim Gunn says, “Make it work.”

Does life really follow the laws of cause and effect? If you’re asking that question, you’re no doubt making movies in Budapest or Rangoon.

- American movies are (with notable exceptions) irony-free.

Hollywood goes for The Big Finish. The lump in the throat, the orphan saved from the storm, the ninth-inning grand slam.

This is because our homegrown flicks believe in (and traffic in) the American Dream. So Harry finds Sally, Luke blows up the Death Star, Ripley whacks the Alien. In Walla Walla or the West Village, audiences would be furious if these movies ended any other way.”

-Chapter 60

My thoughts: Optimism is an easy sell, so it’s no wonder how/why we export it on the global scale.

Hollywood Storytelling, Part Two

“Robert McKee articulates this commandment:

“Thou shalt not take the climax out of the hands of the protagonist.”

What he means (and I agree completely) is, don’t let your hero go passive in the movie’s culminating crisis. Don’t have some other character rescue him or her. Vin Diesel has to save the day in any movie with Furious in the title. James Bond must take down Spectre and no one else.

But this axiom, too, is thoroughly American.

It adheres to and celebrates the American Dream.

French movies frequently violate McKee’s commandment, as do films from Scandinavia or Africa or Russia or Iran or Pakistan, or any Middle Eastern country.

Indian movies don’t (at least the mainstream ones) but then the Indian Dream is more American even than the American Dream.”

-Chapter 61

Write for a Star

“What makes a role for a star?

- His or her issues drive the story. Theirs and nobody else’s. Every character in the story revolves around him or her.

- His desire/issue/objective is (to him, in the context of his world) monumental. The stakes for him are life and death.

- His passion for this desire/issue/objective is unquenchable. He will pursue it to, as Joe Biden might say, the gates of hell.

- At the critical points in the story, his actions or needs (and nobody else’s) dictate the way the story turns.

- The story ends when his issues are resolved (and no sooner).

Here are three roles played in the past few years by Matthew McConaughey: Ron Woodroof in Dallas Buyer’s Club, Mud in Mud, Rust Cohle in True Detective. Each character’s issues drive the story. Each character’s passion is unquenchable. Each character is a star.

Put that kind of role in the center of your story and everything else will fall into place.”

-Chapter 62

Write for a Star, Part Two

“The character must undergo a radical change from the start of the film to the finish. She has to have an arc. She must evolve.”

-Chapter 63

Big Theme = Big Star

“The more powerful the theme, the more powerful the starring role that will carry it.”

-Chapter 76

My Overnight Success

“I’m fifty-one years old and my first novel is being published.

It was easy.

Why?

Because in writing that work, I was bringing to the field of fiction all the principles I had learned in twenty-seven years of working as a writer in other fields, ie. writing ads, writing movies, writing unpublishable fiction.

- Every work must be about something. It must have a theme.

- Every work must have a concept, that is a unique twist or slant or framing device

- Every work must start with an Inciting Incident

- Every work must be divided into three acts (or seven or eight or nine David Lean sequences).

- Every character must represent something greater than himself/herself.

- The protagonist embodies the theme.

- The antagonist embodies the counter-theme.

- The protagonist and antagonist clash in the climax around the issue of theme.

- The climax resolves the clash between the theme and counter-theme.

I had learned these storytelling skills.

But other capacities that I had also acquired over the preceding twenty-seven years were even more important.

These were the skills necessary to conduct oneself as a professional – the inner capacities for managing your emotions, your expectations (of yourself and the world), and your time.

- How to start a project

- How to keep going through the horrible middle.

- How to finish

- How to handle rejection

- How to handle success

- How to receive editorial notes.

- How to fail and keep going

- How to fail again and keep going

- How to self-motivate, self-validate, self-reinforce

- How to belief in yourself when no one else on the planet shares that belief.”

-Chapter 76

My thoughts: These are hard won lessons that come with the struggle, the muscles that are developed. You can’t buy them There’s no quick fix. They come with time and pain.

Narrative Device

“Narrative device asks four questions:

- Who tells the story? Through whose eyes (or from what point of view) do we see the characters and the action?

- How does he/she tell it? In real time? In memory? In a series of letters? As a voice from beyond the grave?

- What tone does the narrator employ? Loopy like Mark Watney in The Martian? Wry and and knowing like Binx Boiling in The Moviegoer? Elegiac like Karen Blixen/Isak Dinesen in Out of Africa?

- To whom is the story told? Directly to us, the readers? To another character? Should our serial killer address himself to the detective who has just arrested him? To his sainted mother who believes he’s innocent? To the judge who’s about to sentence him to the electric chair?

These questions are make-or-break. If we get our narrative device right, the story will tell itself.

Here’s one principle that’s helped me:

Narrative device must work on-theme.”

-Chapter 79

Flashback: A Novel has to Have a Concept

“Remember a concept has to have a spin or a twist, a unique and original framing of material.

The concept of The Big Lebowski is “Let’s take the genre of the Private Eye Story but make our hero not a hard-bitten detective but a sweet lovable stoner.”

The concept of Huckleberry Finn is “Let’s satirize fierce, brutish, small-minded racism of the pre-Civil War South by telling the story of the true friendship between a white boy and a runaway slave through the ironic (though he doesn’t know it yet) cracker vernacular of the boy.”

A great concept gives every word and every scene an interesting, illuminating spin. It takes ordinary and much-used material and makes it fresh.”

-Chapter 89

Flashback: A Novel Has to Be About Something

“We’re talking about theme.

Theme is what the story is about.

Theme is not the same as concept.

A concept is external. It frames the material and makes us look at every element of the material from a specific point of view.

A theme is internal. When we strip away all elements of plot, character, and dialogue, what remains is theme.

The concept of The Sopranos is “Let’s take a gangster and send him back to a shrink. When he whacks somebody, he feels guilty about it. We’ll show a crime boss suffering internally.”

That’s a terrific concept. Other than Analyze This, which treated this idea differently, it had never been done before.

That’s the concept of The Sopranos. The theme is “All of us are crazy in the same way. A gangster’s internal turmoil is exactly the same as that of every other affluent suburbanite with a family and a job. The only difference is our protagonist regularly kills people.”

-Chapter 90

My thoughts: Which is why The Sopranos and other masterpieces of the TV/film work. They show us a mirror in which we see ourselves even though the characters and worlds may be galaxies away.”

What say you?