Logline of The Zone of Interest: The commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss, and his wife Hedwig, strive to build a dream life for their family in a house and garden next to the camp.

Script Can Be Found Here

The Zone of Interest Summary:

The Zone of Interest presents a WWII slice-of-life of commandant Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), and their five children in their rural German villa. All seems well with servants handling their chores and affairs of the house except for one thing of huge note: just beyond their garden wall is the Auschwitz concentration camp.

They may hear occasional tortured screams and receive seized belongings (like a fur coat) from the prisoners, but they pay no mind to the mass cruelty just next door. For instance, when he and his nine-year-old relax in the Sola River, he finds a human skull and seems only perturbed that his officers have disposed of human remains so carelessly.

Upon his promotion to deputy inspector, he learns that he will have to relocate to Oranienburg near Berlin. When he tells Hedwig, she protests as she is deeply attached to the home: she pleads for him to convince his superiors to let the family remain. She receives her request. When Hedwig’s mother Linna stays with them, she at first seems nonchalant about the concentration camp, but decides to leave upon seeing the nighttime flames of the crematorium. Höss also has a secret sexual encounter with a red-headed prisoner.

Months later in Oranienburg, Höss is put in charge of deporting Hungary’s seven hundred thousand Jews for extermination at Auschwitz, enabling him to be with his family. The film ends with him leaving his office; he attempts to vomit but cannot manage to do so. Flashforward to the present, and janitors clean the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. There’s another flashback, and Höss descends a dark stairway.

What does “The Zone of Interest” do well?

This list may not be as long as the others that I’ve done (here and here), but that’s okay. There’s a major thing that this film does extremely well, namely:

- Juxtaposition of mass-scale cruelty with everyday living. Upon reading that Rudolf Höss, his wife Hedwig, and their children were enjoying pastoral family time while, literally, thousands of people were being tortured on the other side of the garden wall made my skin crawl. While most of the characters in the Höss household seemed morally justified in blatantly ignoring the plight of the Jews, I didn’t. I felt so much tension in all of the Villa scenes, and I think it’s a testament to brilliant writing: one doesn’t need to see the killings en masse; the power of (horrifying) suggestion is all you need. Not only does it play upon the conscience of the audience, but it reminds them that inhumanity exists everywhere; the audience, unlike any movie’s characters, can choose to see it and act accordingly to stop it.

- Less is more. Along similar lines, when the Red-Headed Woman appears before Rudolf, she doesn’t say anything. There isn’t an introduction, a name given, or any dialogue said. That Rudolph stays on the phone (and “she takes off her (sic) shoes”) is a power move; he’s in control, and she’s not. Finally, when he “Puts his hands on his hips and sways lasciviously,” we know what’s up (later confirmed by him sneaking back into the villa, disrobing and “scrubbing his genitals”). Anything more said or done would’ve unnecessarily defused the horrifying tension.

- Shades of Grey. What’s interesting is that a man of such extreme cruelty is kind to his wife (save for the adultery), children, and horse; he never beats or lashes out at them (and even makes an arrangement that he’ll go to Berlin while the family stays in Auschwitz). This contrast is key because, in fiction, shades of gray create more narrative mileage for the creators; it also serves to remind the audience that some of the greatest killers in the history of narrative cinema (or even fiction) were refined (think Hannibal Lecter). Contrast is key to creating character complexity (say that three times fast).

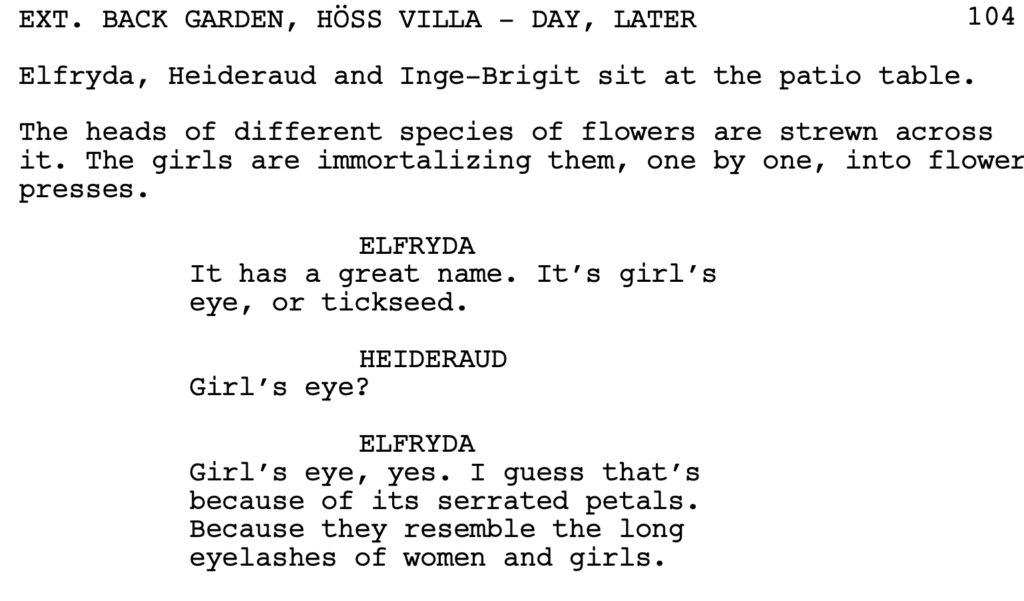

- Parallel symbols. When Rudolf takes out and examines the human eye socket, this symbol sets up the flower press scene among Elfryda, Heideraud and Inge-Brigit. According to the text,

Given that this feels like a payoff to what was set up earlier with the eye socket, this feels like a gruesome juxtaposition, reinforcing just how horrifyingly close the evil and the mundane can co-exist.

Which is the whole point of the movie.

We often think that the evils of the world occur in lands we’ll never visit to people we’ll never meet. Zone of Interest shows us otherwise; that true human cruelty happens in plain sight, and we’re just too blind, ignorant, or scared to do anything.

I can’t remember a screenplay giving me such a visceral reaction (and I see why the film bills itself as a horror film). That being said, I don’t think I can watch this film.

Open to your thoughts…