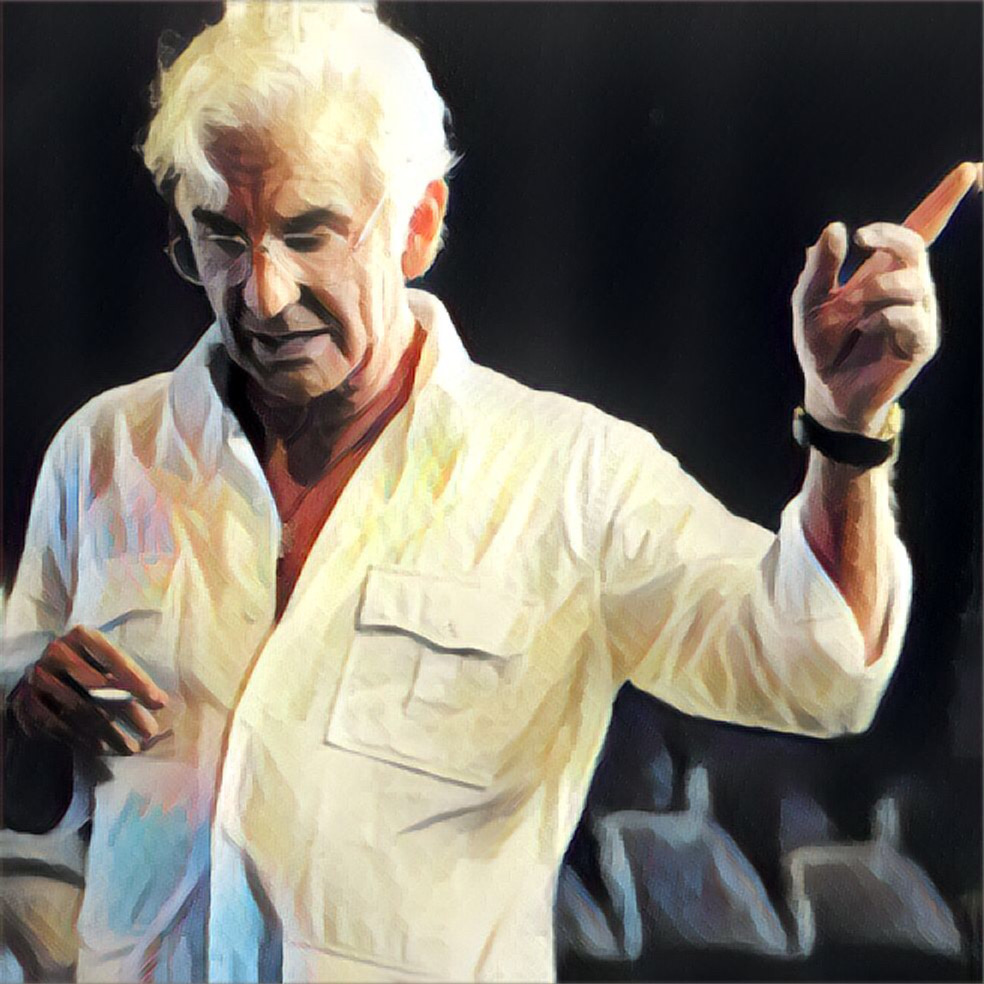

Logline of Maestro: The life of the legendary composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein and his complicated, decades-long marriage to Felicia Montealegre.

Script Can Be Found Here

Summary of Maestro:

Maestro begins with Leonard Bernstein (a.k.a. LB; played by Bradley Cooper) giving an interview to PBS in 1989, playing the piano and talking about his deceased wife. The movie then flashes back to 1943. After waking up next to a male lover, LB receives a phone call that he is to substitute for Bruno Walter with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall that night. He gives a powerhouse performance, and, after a party, he meets and courts actress Felicia Montealegre-Cohn (Carey Mulligan). They continue dating (with romantic trips to Tanglewood, etc). They marry and have kids; he still flirts with men, but Felicia doesn’t really say anything about it; that is, until there’s a party at their apartment and LB saunters away with a young man to make out with on another floor. Upon discovering them, she expresses her hurt-filled embarrassment and Jamie (Maya Hawke), their daughter, begins hearing rumors of Leonard’s behavior, but Leonard comforts her, saying that people who say such things are jealous. As Leonard finishes Mass, and announces it to all of their guests in their Fairfield, Connecticut house, Felicia jumps fully-clothed into the pool. With their marriage officially on the rocks, they nevertheless stay together and continue pursuing their art. When Felicia’s diagnosed with breast cancer, LB stands by her until the end. After her death, he continues to work on his oeuvre and, by the end of his life, he continues creating and cavorts with a younger Black conductor at Tanglewood. The film finishes with the PBS interview, an image of Felicia, and footage of the real Leonard Bernstein conducting.

What does Maestro do well?

- Open Secret – What’s interesting about Maestro is how the piece handles the open secret about LB’s extramarital dalliances. Felicia feels conflicted, but she never reaches an over-the-top melodramatic boiling point (except for jumping into the pool). She never mentions “gay” or “bisexual”; upon discovering him making out with Tommy in the hallway at the party, he apologizes to which she merely says, “Fix your hair. You’re getting sloppy” (p. 53) the subtext of which could very well be “I know about this, but don’t embarrass us.” Later, she mentions, “You prance around with your dewy-eyed waiters that Harry corrals for you, under the guise that they have something intellectual to offer you, while you are, dare I say, ‘teaching’ them” (p. 74). Here, less is totally more, and this reliance on subtext adds so much appropriate tension and contributes to even more complexity in her character.

- Indelible Expression of Anger – When Felicia throws herself in the pool fully-clothed, that’s a stunning visual representation of her anger. As she sits underwater, we can feel how claustrophobic she is in the relationship. For film, this is a way stronger representation of anger than mere shouting, which is really just kept to one scene.

- Portrayal of Creative Genius – When LB and Felicia watch the sailor erotically dancing, and that sailor is LB, it was a beautiful representation about the joys of what it’s like to be creative. The film also touches upon its pain. When Felicia mentions that, “Hate in your heart, and anger– for so many things, it’s hard to count– that’s what drives you. Deep, deep anger drives you. You aren’t up on that podium allowing us all to experience the music the way it was intended. You are throwing it in our faces……how much we will never be able to ever understand and by us witnessing you do it so effortlessly, you hope that we will know, really know, deep in our core, how less than we all are to you” (p. 74). Yet this portrayal of a creative is not stock; he doesn’t demonstrate rage or anger in obvious ways; he just pours it out in his music and believes that “an artist must cast off anything that’s restraining him. And an artist must be resolute in creating, with whatever time he has left, in absolute freedom” (p. 76).

- Understated Death – When Felicia passes, it isn’t some long drawn-out scene with tons of melodramatic cliches or over-the-top emotion. Instead, he hugs her in bed, then there’s an image of him looking out at the sea wall, and LB and the kids drive off. This understatement counterbalances the seriousness of the event, refusing to let the film lapse into something maudlin.

Overall, this was a good vehicle for Bradley Cooper. (I couldn’t help but wonder if Hollywood loves films about such tempestuous creatives because it feels seen).

Thoughts?